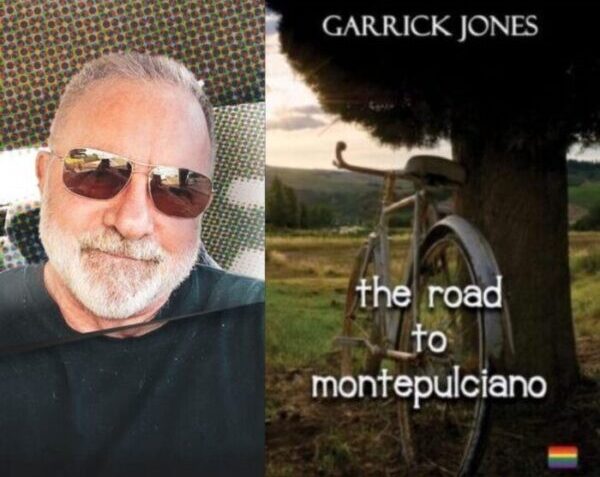

An excerpt from The Road to Montepulciano

Check out Garrick’s website: https://garrickjones.com.au/

Available on Amazon Australia UK USA

Sunday 2 April, 1950

“Ehi! Inglese!”

I was looking out of the window on the left-hand side of the bus, watching the fields go by. It was the first time we’d stopped since leaving the town.

I’d been sitting on the long bench seat at the back, my head leaning against the window, my rifle between my knees, and my haversack stowed in the netting above that served as a luggage rack. I checked my watch. Had I really only left Pienza ten minutes ago?

Stumbling past a string bag of live chickens and a few boxes people had stowed in the aisle, I reached the front of the bus. “Stop. Here. I?” I asked with a cheeky grin, trying to cover up my truly dreadful knowledge of the language of the country in which I intended to live.

“Vai!” the bus driver said, batting the air with the back of his hand, laughing at my fractured Italian. Once on the road, I turned to thank him, but the pneumatic door hissed shut in my face. I said it anyway, giving the driver a mock bow. I could see his broad grin through one of the glass panes of the door.

My rifle slung over my shoulder and my haversack between my feet, I took out my pipe, tamped and lit it, then leaned against the signpost at the T-junction where I’d asked to be let off. Well, I hadn’t asked—I’d thrust the map in the driver’s face and stabbed my finger at the place where I needed to alight. The bus driver honked the horn and drove off. I waved, watching it kick up dust on the dirt road as it headed to the east.

Three indicator signs sprouted from the top of the post. To the west, Pienza, from where I’d just come: 6.5 kilometres away. Montefollonico to the north: 5.1km. And to the east, along the road I was to follow, Montepulciano: 8.6km.

The three towns were relatively nearby. The house, although I’d only seen a photograph of it, had been described as being ‘in a good position’. At the time, I’d convinced myself that it was a good buy. The grainy postcard-sized photograph the auctioneer in Siena had given me showed it to be neglected, but not a total ruin. I hoped that was true; I’d spent almost the last of the money I’d kept in the bank for emergencies on a hasty bid for a farmhouse that no one else seemed keen to buy. One hundred and thirty thousand lire had seemed a lot until I’d converted it—first to American dollars then to Australian pounds. A hundred quid or thereabouts was a pittance for a house on five hectares of land. The only proviso to the sale was that I had two years to clean up the house and the garden, otherwise I’d forfeit it, be kicked out, and it would be re-auctioned by the Province of Siena—that much I’d understood from the notary who’d witnessed my signature and who spoke basic English. I’d also been given a list of things to be done as part of the deal, almost a page long, but hadn’t bothered to try to translate it yet. All in good time.

The scenery on the left-hand side of the road had been beautiful, just as I’d imagined Tuscany to be: broad fields dotted with copses of trees, sweeping vistas, and blueish-hazed low hills to the east. Lining both sides of the road were sparse clusters of ash, poplar and hazelnut, interspersed every so often by flowering trees. I recognised the white blossoms of almond and the pale pink of peach and cherry. It was far too early for apples or pears, and no doubt, just as in Vence, in France, where I’d been living for the past year and a half, they’d been seeded by pips and stones thrown from bus windows.

I moved away from the signpost, settling my bum on the low stone wall next to it, cool against the backs of my legs and my arse, the sun warm on my chest, arms and face, and checked the map again. According to the directions I’d been given by the auctioneer, the house was on the right-hand side of the road to Montepulciano, two hundred and fifty metres from the T-junction. My cold backside eventually told me that it was time to move, so I picked up my haversack and my rifle and headed in that direction. A man rode past on a donkey, staring at me oddly, not replying to my “Ciao!”. I shrugged and kept walking.

The wooden gate held fast. It was one of those wide affairs: planks fastened to a Z-shaped frame. I shoved and heaved at it, frustrated, until I leaned over and saw that short blocks of wood had been nailed from the gatepost to the gate frame. I threw my haversack over, placed my rifle next to it, then climbed over and made my way towards the house, the chimneys of which I could see over the cluster of olive trees that hid it from the road.

It was just as the written description had said it would be, and how I’d imagined it for the past ten days: stone walls, two storeys high, with a terracotta tiled roof—a few tiles missing at the front on the western side—the windows shuttered and the chimneys capped. A large area of golden dry grass and a tall pine, branchless up to about twelve feet from its base, stood at its front. It was quiet—very quiet—just the sort of place that would suit me down to the ground. A month in bustling, crowded Siena had made me feel restless. I’d got nothing done; here I could write and draw and hopefully start a new life.

The front door was immovable, so I made my way around to the back of the house. The kitchen was a lean-to, possibly a later addition to the main house, although sturdily constructed from the same building materials. Its door wouldn’t budge either. As I ran my hand down the edge my finger caught on something sharp—the point of a nail. It didn’t take a genius to figure out that the door had been nailed shut with wooden blocks, just like the front gate. But why?

Well, if the doors had been nailed from the inside, the person who’d done it had to have been able to get out of the house, so I started working my way around, trying the shutters of the ground-floor windows.

One, at the northeastern side of the house, next to the kitchen addition, abruptly gave way and flew open, smacking me in the face and knocking my pipe from my mouth. The windows behind the shutters were timber-framed, each with three large glass panes, similar to those of the small house in France in which I’d been living until a month ago. They opened inwards. I hoisted myself onto the sill, then dropped into a small room. It was bare except for a table with four chairs and a sideboard, everything covered in a thick coating of dust. A door opened into the kitchen, which proved to be a wreck, the brick stove completely smashed, its iron cooktop leaning perilously against the wall. The pump over the stone sink looked rusted; I gave it a few quick strokes but heard nothing but hollow sounds. Perhaps it needed priming.

Opening the window above the sink, I unlatched the shutters and threw them back. Light flooded into the kitchen. Looking around, I smiled, rather pleased with what I’d found so far. Having spent most of my life on a farm, I could turn my hand to anything; nothing I’d seen so far looked beyond repair. I relit my pipe and leaned against the edge of the sink, surveying the tangle that had once been a garden.

Something scuttled in a room at the front of the house. Rats? I snorted. Nothing a cat wouldn’t sort out—I liked cats, they made good company. Undemanding, except for food, just like me. I wasn’t sure how I turned out to be so laid-back, especially in view of my life so far, but nothing much disconcerted me these days.

Following the sounds, I passed an empty larder—its shelves bare and its floor caved in—then moved a heavy curtain to one side, leaving it to fall closed behind me. It felt rather more like a rug than something made from fabric. I stood in the pitch dark for a moment, then shuffled carefully with one outstretched arm towards the far wall of the room in order to see whether I could open one of the windows and push back the shutters to let in some light.

My foot hit something. The sensation was not entirely unfamiliar to me. The slight resilience of the object as I prodded it with the toe of my shoe told me exactly what I’d stumbled across. Instinctively, I cursed and jumped back a step.

My Zippo, lit and held aloft, revealed a body. A man, perhaps in his late thirties, lying on his side, his hands tied behind his back, gagged, and shot in the back of the head. In the dim light I saw a fan of blood and brain matter sprayed out over the dust in front of his face. I was also standing in a dark patch—presumably more blood.

I clucked my tongue. I’d seen my fair share of death during the war, but now, five years after it was over, I’d become unused to the sight.

I crouched, holding the lighter closer to the body. Using the back of my hand, I lifted the side of the man’s head: the right eye and cheekbone were missing. The gun must have been held very close to the back of his head.

“Ah, Jesus!” I whispered, then crossed myself when I moved in for a closer look. The lighter revealed the glimmer of wetness in and around the wounds and there was blood on my hand. Carefully, I grabbed the man’s calf, bending his leg at the knee to test for rigidity. It wasn’t stiff; rigor mortis had yet to set in. He couldn’t have been dead for more than a few hours.